A just transition for the gas industry and its workers

SUMMARY

Gases will continue to play a vital role in Europe's domestic energy production, with an increasing focus on hydrogen and biomethane. This will help to meet climate goals, reduce dependence on third countries and provide affordable, secure energy for industry, its workers and citizens.

By Charles EllinasEurogas, EPSU and IndustriAll Europe published a new report on January 26, entitled Towards a Just Transition for the gas sector and its workers, aimed at identifying the challenges around a just transition in the European gas sector. The report was presented by the three partners at a conference in Brussels. The report includes a number of important recommendations around scaling up hydrogen, biomethane and carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS), concluding that “gases will continue to play a vital role in Europe's domestic energy production, with an increasing focus on hydrogen and biomethane. This will help to meet climate goals, reduce dependence on third countries and provide affordable, secure energy for industry, its workers and citizens.” An important part of it are recommendations for a just transition for the sector’s current workforce and future skills planning based on social dialogue.

From left to right: Jan Willem Goudriaan, EPSU general secretary, Judith Kirton-Darling, IndustriAll Europe deputy general secretary, and James Watson, Eurogas secretary general, presenting the conclusions from the conference.

A successful energy transition and the decarbonisation of energy systems and industrial sectors is one of the most important challenges Europe will face in the run-up to net zero by 2050. As Eurogas secretary general, James Watson, said: “transformation is inevitable, and getting it right is essential.”

The nature of the transition, and its economic and social impacts, will differ from region to region depending on sectors, industries and resources. Ultimately it will also impact workers and job security across the EU. This is particularly true in the energy sector and especially the oil and gas industry. The transition will not happen overnight – it will take time and will need to be managed properly.

The socio-economic risk must be tackled to protect workers throughout the energy transition. The Paris Agreement recognised that policy implementation should take into account “the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs”.

The International Trade Union Confederation has defined a just transition as a transition that “secures the future and livelihoods of workers and their communities in the transition to a low-carbon economy. It is based on social dialogue between workers and their unions, employers, and governments, and consultation with communities and civil society.”

The joint project made recommendations on how to achieve a just transition. These could be implemented at the European, national, regional or company level. They all follow the same logic of identifying what already exists, mapping possible future scenarios, and devising the best methods for achieving it. These include:

-

The methodology to be implemented to understand future challenges.

-

Social dialogue as a key element in ensuring a just-transition.

-

Training as a major factor in the transformation of jobs and profiles.

Understanding the correlation between the future needs and the resources available will invariably require concrete actions, such as professional training, identification of career paths and making links between jobs - such as cross-sector recognition of qualifications.

The gas sector suffers from a lack of attractiveness due to a negative perception of fossil fuels and a lack of understanding about the professions within the sector. Fostering the competencies needed for the shift towards net zero, the attractiveness of the sector must be improved.

The report concludes that delivering a just transition for workers will be challenging. Adaptable tools for anticipation, monitoring, solid social dialogue and collective bargaining will be crucial to achieving it.

An industry at a crossroads

Both Eurogas and the European Commission foresee an important role for gas in the transition. It plays a very important role in the EU's energy mix andprovides storage, flexibility and security as Europe works towards its climate targets.

Eurogas is determined to fully decarbonise gas networks soon after 2045. Looking across energy networks and sectors, cost-effective decarbonisation is going to require coordinated infrastructure planning and a just-transition for its workers.

The gas sector offers an efficient transition pathway to phase out more emission intensive sources of energy like oil and coal, but it must also tackle the emissions resulting from the extraction, production, transport and use of natural gas.

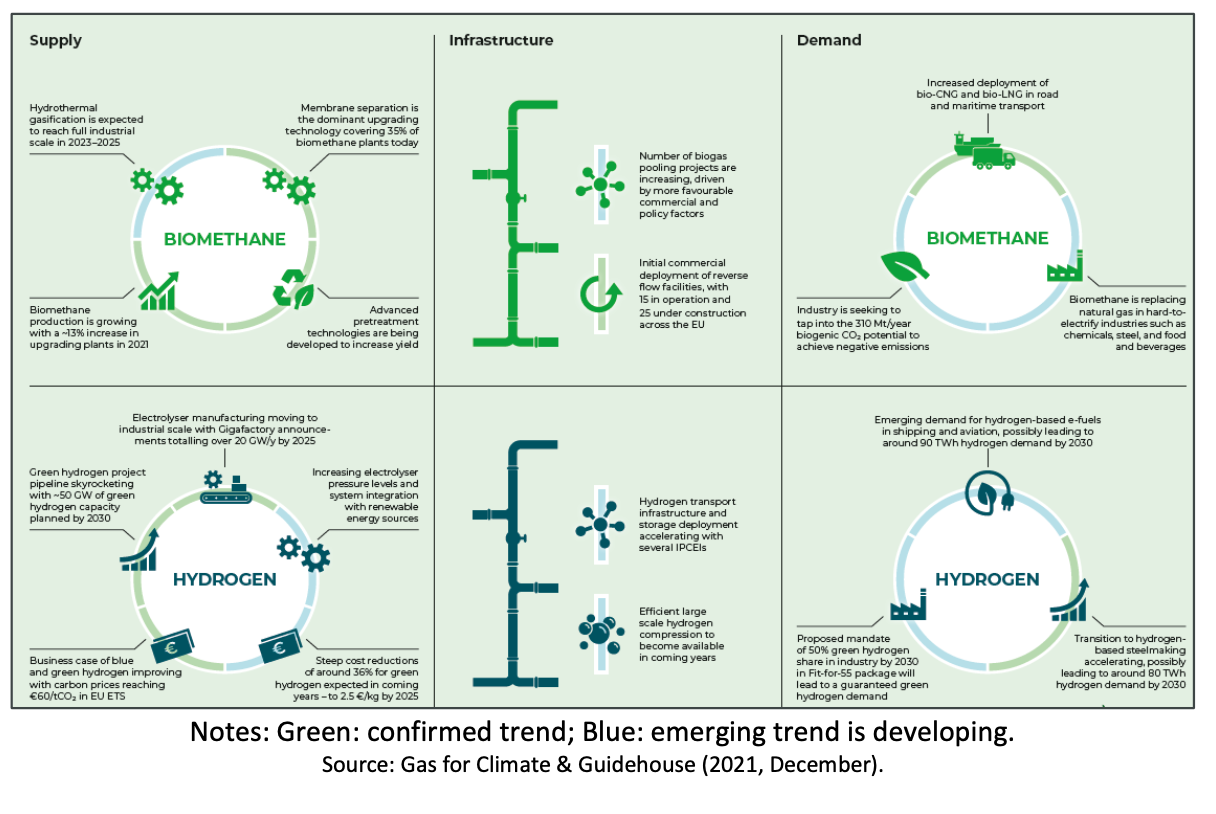

The main routes to decarbonise the gas sector rely on switching from natural gas to other commodities, such as biogas and hydrogen (see figure 1). Both have an impact on the sector’s infrastructure, technologies and skills needed in the future.

Figure 1: Key trends in biomethane and hydrogen in Europe

Biogas is mainly biomethane that has the advantage of being able to be transported and distributed in existing gas grids without any retrofitting. At present, the total injection of biomethane into the gas grid is less than 1% of the current demand for natural gas in Europe. However, REPowerEU expects this to grow rapidly, targeting 35bn m3/yr of biomethane by 2030. Achieving this requires a 35% average annual growth rate from now to 2030.

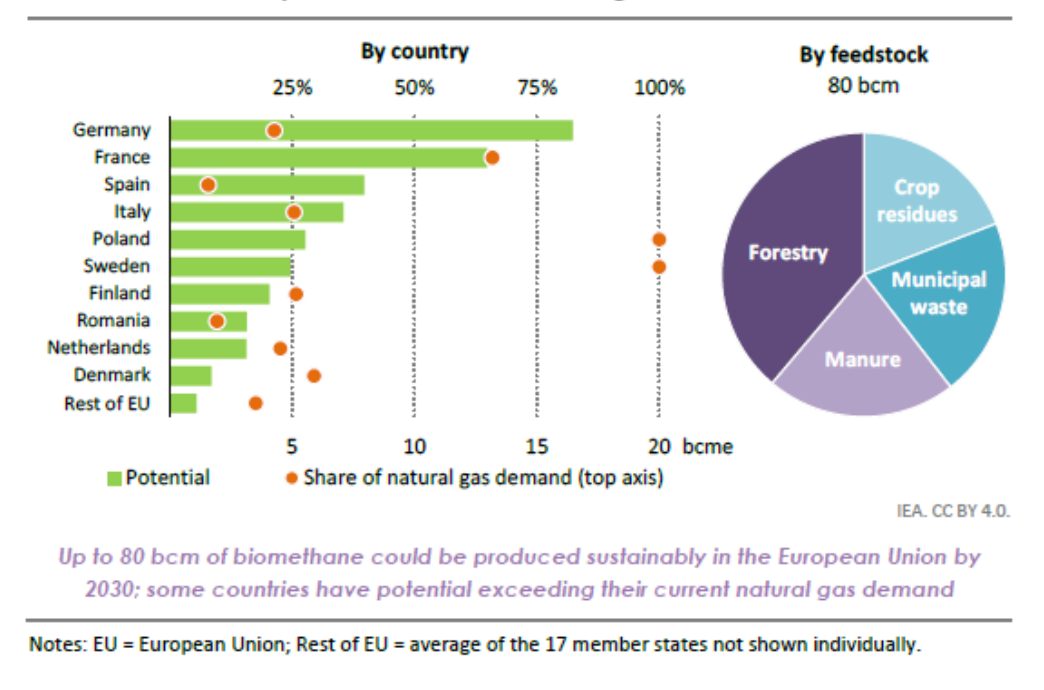

The EU is supporting the scalingup of biomethane, and there is significant potential across the region (see figure 2). The most optimistic forecast predicts supply of 151bn m3/yr of biomethane by 2050, provided the right conditions are fulfilled. The enormity of the task becomes clear when one realises that currently only around 3bn m3/yr of biomethane and 9bn m3/yr of biogas are produced.

Figure 2: Biomethane potential in the EU by 2030 versus share of natural gas demand in 2021

Hydrogen is another commodity expected to grow rapidly in Europe. But compared to biomethane hydrogen is more challenging to transport and distribute. By the end of 2021 global annual hydrogen demand increased to 94mn metric tons, but, out of this, low-emission hydrogen was less than 1mn mt.

The two forms of low-emission hydrogen are blue hydrogen produced from natural gas using CCUS, and green hydrogen produced from renewable electricity using electrolysis. The EU is placing special focus on green hydrogen. It set a target to install at least 40 GW of renewable hydrogen electrolysers by 2030 and produce 10mn mt of green hydrogen, with another 10mn mt of imports, by 2030. However, the International Energy Agency (IEA) pointed out in its 2022 Global Hydrogen Review, that so far growth of green hydrogen has been slow and must be accelerated substantially if the levels needed to achieve 2030 targets are to be achieved.

But even then, commercialisation and deployment of green hydrogen on a large scale face significant challenges with regards to production, storage, transport and distribution and end-use that need to be addressed in order to bring costs down and improve competitiveness.

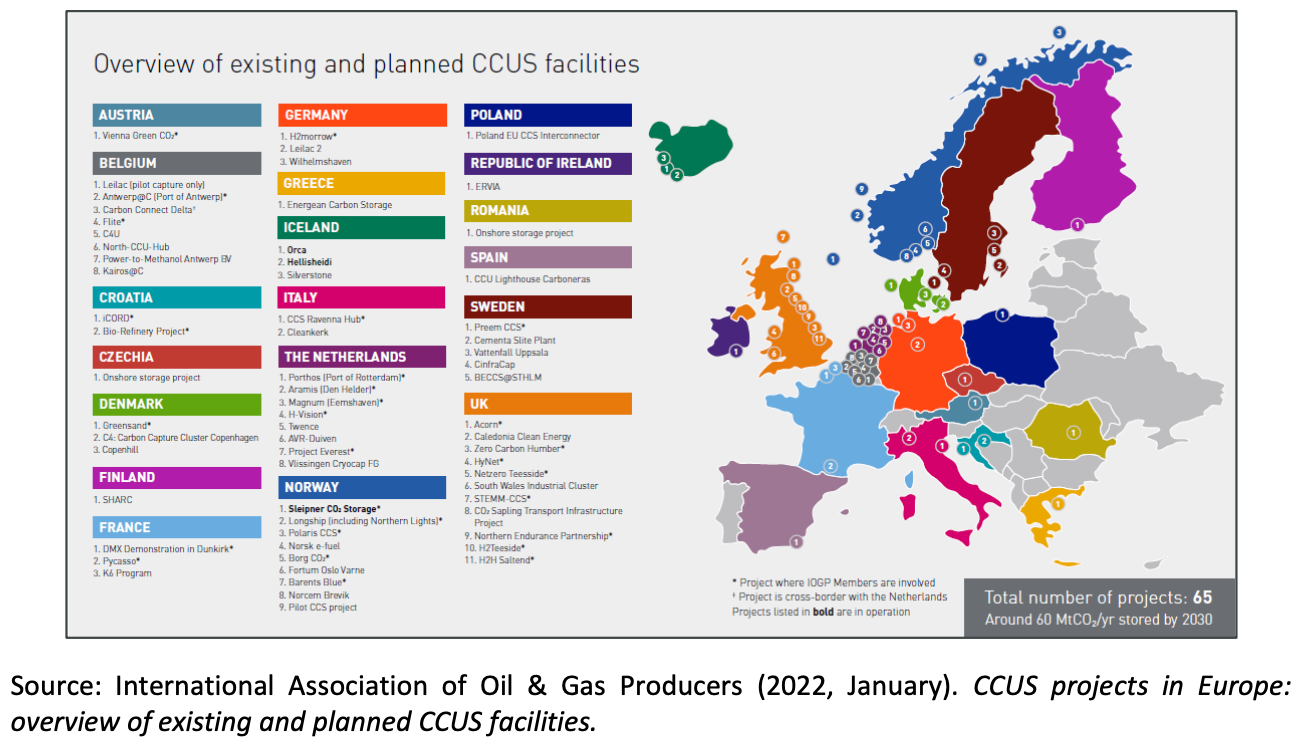

CCUS technologies, needed to produce blue hydrogen and capture industrial emissions, have also taken on new momentum in Europe (see figure 3). However, the EU Taxonomy only supports investments in CCUS for hydrogen production, and not for its other uses, limiting the development of a competitive CCUS industry. Deployment and operation currently remain limited.

Figure 3: CCUS projects in Europe

The above indicates that the gas industry is at a crossroads, with its longer-term future depending on scaling up different technologies. The war in Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis could act as an accelerator of change in the sector, but these crises also bring uncertainty.

The REPowerEU targets demonstrate the willingness of the EU to speed up development of green hydrogen and biomethane technologies. But EU policies are still unclear regarding what is expected for natural gas by 2030 and beyond. Mixed messages and signals by the EU and the US to stop investing in new oil and gas fields and accelerate transition to cleaner fuels are holding back energy investments sowing seeds for future energy crises.

Mike Wirth, Chevron’s CEO, summed up the industry’s concerns when he said in October 2022 a premature effort to transition from fossil fuels has resulted in “unintended consequences”, including energy supply insecurity. With variable, intermittent, renewables in mind, he warned that Western governments have made a global oil and gas crunch worse by doubling down on climate policies that will make energy markets “more volatile, more unpredictable, more chaotic.”

During energy transition, and until renewables reach the levels and reliability required to replace fossil fuels – and until prolonged intermittency is dealt with – oil and gas production will need to be maintained if the world, including Europe, is to avoid frequent energy crises.

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had a major impact on the European gas sector. It has significantly impacted the supply and demand of natural gas, and these changes could become permanent if, for example, heavy industries move outside of Europe. The ever- changing geopolitical situation makes it difficult to assess the future evolution of gas demand in the EU over the next 10 to 30 years.

Methodology to achieve a just transition

The report states that “when we talk about a just energy transition, we are referring to a scenario where the value of the worker in the fossil energy sector does not disappear but is transformed and redesigned according to a market diversification.”

The methodology must be multi-faceted, starting with mapping the current situation and the identification of the major trends, and ending with mapping the gaps between current skills and those needed in the future.

The process must start with a diagnosis that is as factual as possible. It should include an in-depth reflection on jobs through a comprehensive mapping of existing jobs and skills and should map the various medium-term scenarios of how the sector could evolve. It is important that these scenarios are comprehensive, but also realistic, especially in view of the fast changing geopolitical and commercial landscape.

This methodology comprises five steps, each of them relying on the fruitful cooperation of social partners:

-

Adopting a methodology built with the social partners to guarantee its effectiveness and adherence

-

Carrying out an inventory of jobs and skills in each European country

-

Building scenarios for the evolution of the gas sector according to national and also local specificities

-

Identifying future changes on jobs and skills needs

-

Building career paths and identifying business bridges within the sector and with the outside world.

The outcome should then be shared. Social dialogue at all levels is key.

Social dialogue and training

Social dialogue will be a decisive step in the process of achieving a just transition, as the feedback from local institutions, companies, and staff representatives is one of the keys needed to successfully construct forecasts.

These forecasts must be realistic, i.e., with a significant probability of being achieved, and linked to employment and the energy transition.

The developed scenarios will then enable identification of needs in terms of skills and the workforce, making it possible to define the required HR tools.

In order to be successful, this process must account for local issues and specificities. The numerous employment areas possible have geographical, economic, and social specificities that will each require different actions and specific support. Making the approach as effective and efficient as possible, means local actions being supported, or even favoured, depending on cultural and political contexts.

Training will be essential to respond to the challenges around hydrogen, biomethane and CCUS. In Europe, hydrogen is set to be a strategic energy vector in the medium term, but it is still in the scale up phase. For that reason, anticipating future needs will involve, among other things:

-

Structuring relevant and clear training programmes for related jobs. These should cover a sufficient geographical area to anticipate, and best respond, to companies’ needs.

-

Training and/or retraining employees in both the gas sector and other sectors to capitalise on their expertise.

Important to this is making full use of best practices of companies and strengthening the links between private and public sectors to support the preparation of training programmes.

Sector attractiveness and diversity

The sector is impacted by a lack of attractiveness due to negative perceptions of fossil fuels, especially by the younger generation.

The report places particular importance on remedying this. Strengthening the attractiveness of the sector, requires communication with public authorities, people and workers living in the EU, particularly as climate issues become more prevalent.

It makes it clear that it is not a question of greenwashing but rather of highlighting values related to the professions, the meaning of the work, and the professional and social elements of recognition that accompany it, including remuneration and working conditions.

Regular communications aimed at the general public and target populations, especially younger people and women, should focus on the role of the sector in the transition and increasing domestic energy production, the potential for job creation and the technical and technological dimensions of the jobs in the gas sector.

Making the gas sector a more diverse and inclusive workplace will help achieve climate and social goals and help improve its attractiveness.