UK makes bold blue hydrogen push

SUMMARY

The overwhelming majority of planned low-carbon hydrogen capacity in the UK is for blue hydrogen, and the oil and gas industry is leading development.

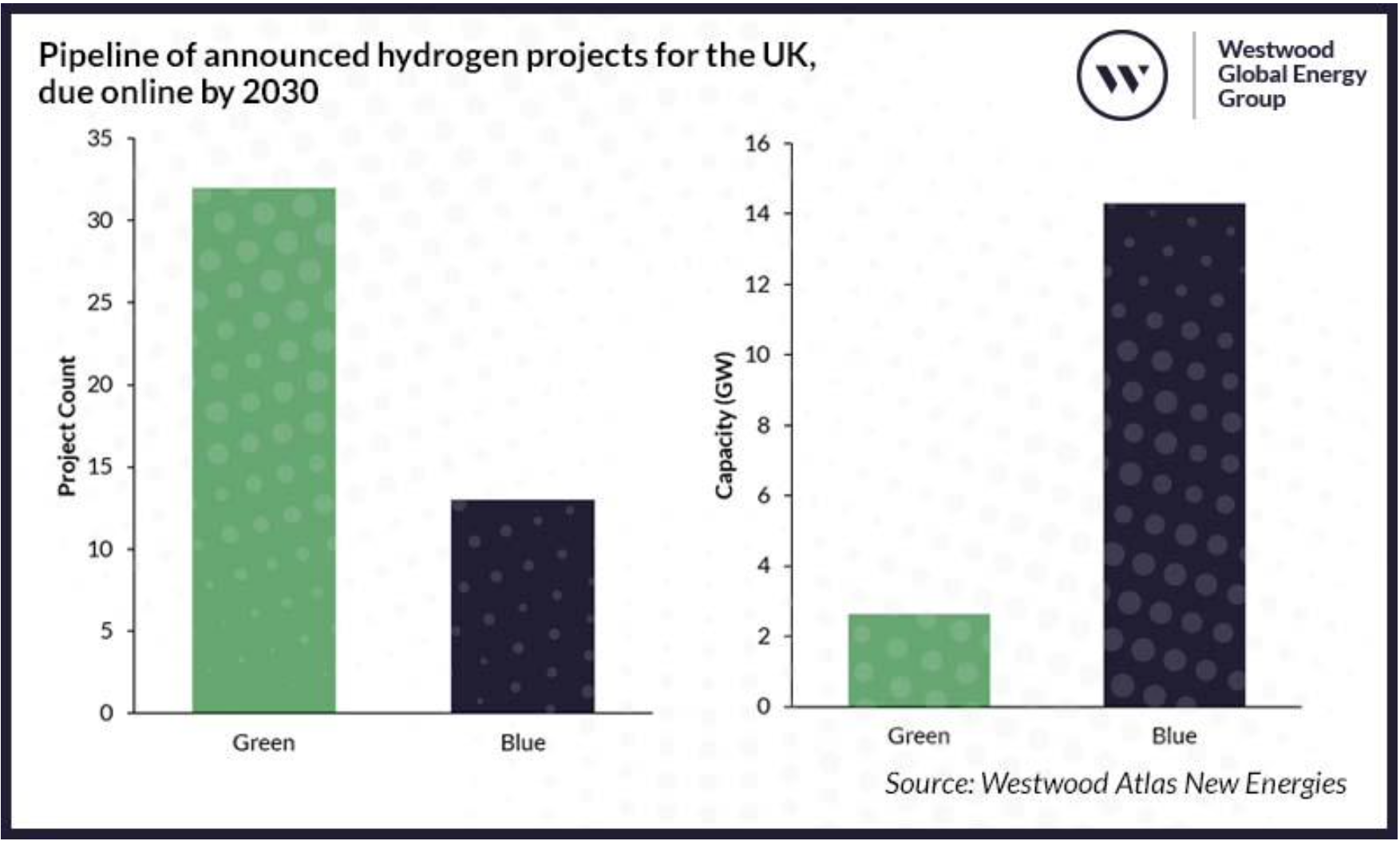

By Joseph MurphyThe UK has a project pipeline that more than exceeds its 10-GW target for low-carbon hydrogen production by 2030, and blue hydrogen, derived from natural gas, accounts for the overwhelming majority of planned capacity, Westwood Global Energy Group noted in a report this month.

Out of the 45 planned low-carbon hydrogen projects in the UK, there may be only 13 blue hydrogen developments, but they will contribute 84% of the 17 GW of capacity announced for start-up by the end of the decade. In the meantime, only a handful of demonstration-sized green hydrogen projects have so far reached a final investment decision (FID), according to Westwood.

Blue hydrogen can be scaled up faster than green because both grey hydrogen production technology and carbon capture are well-established, Westwood said. It can provide the UK “with a route to decarbonisation in the short-to-medium term until green hydrogen is more readily available and cost-competitive,” it said.

Taking the lead in blue hydrogen development are large traditional oil and gas players, demonstrating their key role in the initial scale-up of blue hydrogen, Westwood said.

“These companies have access to existing hydrogen production (at refineries), natural gas supply and pipelines,” Westwood said. “They are also able to leverage their wealth of technical, geological and regulatory expertise needed to progress these projects.”

Spearheading Shell’s blue hydrogen drive. The company is participating in three projects with a combined 3.3 GW of capacity. Vertec Hydrogen, a joint venture between Essar and Progressive Energy, is developing 3.3 GW through its Hynet project, while Equinor is taking part in two projects with a combined output of 1.8 GW.

These projects are all coastal, giving them easy access to necessary natural gas supply and CO2 storage, strengthening their business case, Westwood said. They are also situated close to major clusters of high-emitting industries.

Hydrogen can balance the intermittency of renewables, as well as create value from renewable power generation that would otherwise have to be curtailed. It can also balance seasonal fluctuations in demand and be used for grid balancing, using hydrogen-fuelled combined-cycle gas turbines.

Hydrogen can either be stored in salt caverns and depleted oil and gas reservoirs, and those sites can also be used to store CO2 that has been captured during blue hydrogen production. Salt caverns have advantages over depleted oil and gas reservoirs, which means they are set to be used first, according to Westwood. But the lead-time development for both options takes five to ten years.

As for CO2 storage, the UK will need 104mn metric tons/year of storage by 2050, according to Balanced Net Zero Pathway. The UK fortunately has one of the largest offshore CO2 storage capacities in Europe – some 70bn mt. Over half of this is found in the Central North Sea.

Hydrogen is difficult to transport over long distances as it requires compression or liquefaction, both of which are costly. Therefore, hydrogen has traditionally been consumed at the site where it is produced, and so hydrogen projects in the UK are being developed close to key demand centres – the country’s industrial heartlands.

When hydrogen needs to be transported via pipelines over distances, however, repurposing existing gas pipelines is five times cheaper than building new ones, independent gas supplier National Gas estimated last year.

Risks and uncertanties

Government support has been critical for incentivising hydrogen production in the UK like elsewhere. The UK government’s current support comes in the form of two measures – the Net Zero Hydrogen Fund (NZHF) and the Hydrogen Business Model (HBM).

HZHF is aimed at de-risking investment in production and reducing lifetime costs. It provides £240mn ($284mn) in grant funding to cover upfront costs.

HMB, on the other hand, provides ongoing revenue support to the developer through a contracts for difference (CfD) mechanism, previously used successfully for renewable power projects in the UK.

While the UK is “primed for success,” Westwood said, this is largely down to the government. And there is more work to be done. The consultancy flags up a number of risks and uncertainties that could undermine the UK’s hydrogen ambitions.

Firstly it points to political uncertainty, given that the UK has undergone a series of government leadership changes over the past 18 months, creating financial instability, policy uncertainty and delays. Secondly there is competition for investment with other countries providing hydrogen support. The US has provided incentives in its Inflation Reduction Act, while the EU offers it in its Green Deal Industrial Policy.

There is also an issue with hydrogen definitions. Countries have announced varied low-carbon hydrogen definitions, and there should be mutual recognition of international standards and certification to promote cross-border trade. The UK has begun consultations for its hydrogen certification scheme, which it aims to launch in 2025.

There is also a lack of clarity about future government support – the timing of scope of future HMB and NZHF fund allocation and the Track 2 cluster sequencing programme for decarbonising industry have not yet been defined.

Meanwhile, the Low Carbon Hydrogen Agreement terms for inclusion in HBM is still in draft, and is not expected to be finalised until later this year following delays, while business models for hydrogen in transport and storage infrastructure are planned to be developed for 2025.

Blue hydrogen and carbon capture and storage projects need to move forward in tandem but there are currently timing misalignments between the two business models, making it difficult for developers to reach FIDs.

Finally, the government has not yet determined hydrogen’s role in blending and heating. These decisions, due to be taken in 2023 and 2025 respectively, will potentially have significant implications for future hydrogen demand.

The ‘chicken and egg’ problem

Blue hydrogen projects need to be up and running by 2027 to qualify for government support, which means developers taking an FID by 2024. However, Westwood noted that “few are willing to assume the risk of a binding take or pay contract that is usually required before FID takes place without further guarantees.”

To overcome this ‘chicken and egg’ problem, Westwood suggests that the government could offer non-binding initiatives to offer up more certainty and encourage projects to move forward to the front-end engineering and design phase.

“Clarity, as well as a simplified, streamlined process is needed such that all players along the entire value chain can move in tandem at the pace needed to meet the targets,” the consultancy said.

The UK has numerous advantages it can harness to become a leader in low-carbon hydrogen, Westwood said.

“Whilst risks and uncertainties abound, these can be mitigated to secure investment – strong, clear, streamlined and timely government policies will be key. At the same time the incentives must permeate through all parts of an incredibly complex value chain,” Westwood said. “Competition is quickly heating up around the world and any delay or lack of clarity in the government’s steer could have adverse consequences for the UK’s hydrogen ambitions should investors believe they can obtain greater certainty and higher returns elsewhere.”