Birchcliff takes a LEIP forward on clean gas

SUMMARY

Montney producer is focused on developing lower-carbon natural gas. [Images: Birchcliff Energy]

By Shaun PolczerPOSTED IN:

Birchcliff Energy CEO Jeff Tonken is an unabashed fast-food fan. On this day, he’s espousing a popular burger chain that touts the health and social benefits of hormone-free, grass-fed beef as a selling point for its product offerings – with the added benefit of slowing his (by his own admission) expanding waistline. “Now I’m getting hungry,” he quips.

It may seem incongruous to compare socially-conscious burgers to socially-conscious natural gas – bovine flatulence accounts for only 8% of Canada’s methane output compared to 45% for fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency – but Birchcliff is similarly attempting to distinguish its environmental and social governance (ESG) efforts by designating itself a “low energy intensity producer” (LEIP) in relation to its peers.

“We wanted to develop something that was our own acronym,” Tonken says of the company’s overall ESG efforts. “We asked ourselves, ‘how do we put a badge on it?’”

“We wanted to develop something that was our own acronym,” Tonken says of the company’s overall ESG efforts. “We asked ourselves, ‘how do we put a badge on it?’”

Apart from the vagaries of evolving regulatory requirements and uncertainties surrounding climate change policy, both energy and agriculture have been highlighted as Canada strives for net zero emissions by 2050. Both are being driven by market demand and a growing consumer awareness of how their energy – and food – are produced.

Tonken admits what started off as a branding exercise has become integral to the company’s corporate culture. It’s a competitive advantage, he insists, that gives Birchcliff an edge over its competitors both in terms of how its 78,500 barrels of oil equivalent (boe)/ day is produced and in how it is ultimately sold to consumers.

As he talks, the word “obligation” comes up repeatedly in conversation. An obligation by Birchcliff to reduce its impact on land, air and water as well as an obligation to share the benefits of development in the communities in which it operates – and an obligation to maximise shareholder returns. Apart from purely reducing emissions, Tonken insists LEIP extends through all areas of the company’s corporate culture, including employment, education and training. “Our view is much broader than GHG emissions,” he says. “It speaks to our values.”

Many might call it boilerplate. But it takes more than lofty pronouncements and a fancy logo to make the point, Tonken insists. In that regard, he is proud to boast that Birchcliff is tops among its peers when it comes to managing emissions at an operational level. It takes pains to invest in newer plants and facilities. It strives to stay ahead of the curve – “beyond regulation” Tonken insists – to reclaim leaking abandoned wells and perform maintenance.

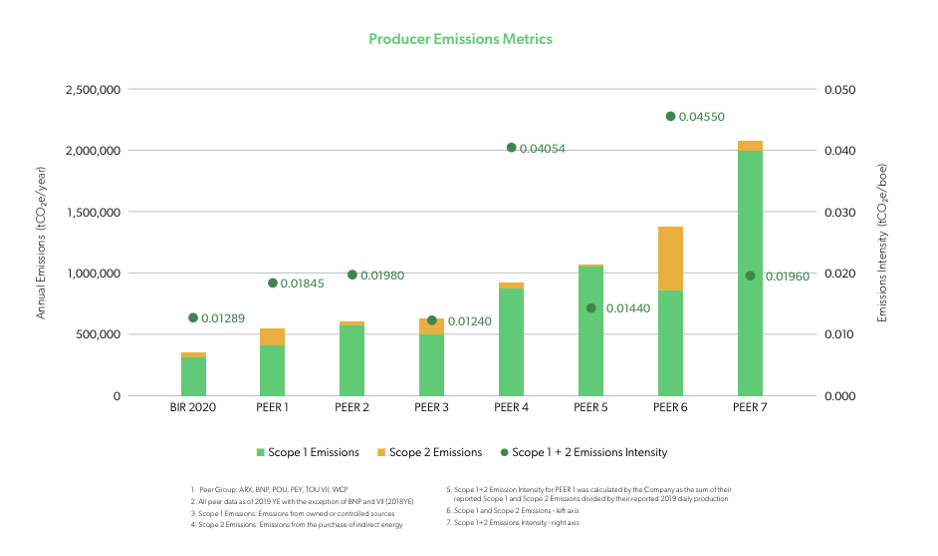

The numbers back up those lofty words. Birchcliff asserts it continues to be one of the lowest GHG emitters in Canada’s oil and gas sector, with a Scope 1+2 emissions intensity in 2020 of 0.0129 mt of CO2 equivalent/boe (mtCO2e/boe), or some 44% lower than its peer group’s average of 0.0230 mtCO2e/boe, based on publicly disclosed data.

Apart from CO2, the numbers factor in other emissions sources such as flaring, stationary combustion, fugitive venting and so-called Scope 2 emissions, defined by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as indirect GHG emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat, or cooling as a result of the organisation’s energy use beyond the field level – heating the company’s corporate offices on a typical -20°C Calgary winter day, for example.

According to its 2020 ESG report, Birchcliff continues to actively reduce its GHG emissions intensity throughout its operations consistent with United Nations’ sustainable development guidelines. This includes its active methane reduction and retrofit compliance plan as well as ongoing carbon sequestration activities combined with a focus on innovation to lower emissions in routine operating practices such as drilling and completions.

While he acknowledges the obvious pressure to meet increasingly onerous regulatory requirements, Tonken firmly believes sound environmental performance also makes sound business sense. In its ESG report, the company says it hopes to start generating emissions credits as a financial reward to shareholders in addition to eventually helping push it to achieve net zero emissions targets while lowering production costs and bolstering its bottom line.

Goalposts

The latter is particularly important given the perception that meeting compliance is necessarily a financial burden. Tonken says the latter point speaks to driving innovation and a quest to find newer cost-effective solutions to age-old problems. Although Tonken – and some of his peers – the goalposts keep moving on Canada’s rather ambitious climate change goals, the basic challenge remains the same: how can the industry innovate itself out of the problem while continuing to survive, and indeed thrive, under a new emissions regime? “Yes, we have a problem. And yes, we will solve it over time.”

To that end, Birchcliff is a partner in the Natural Gas Innovation Fund (NGIF) and its two subsidiaries, NGIF Industry Grants and NGIF Cleantech Ventures Equity Fund – essentially a hedge fund to incubate new start-ups and spinoffs. The word “hedge” is particularly apropos, as industry looks to spread its bets in hopes of finding a silver bullet solution. By investing in and supporting early-stage clean technology companies that develop new technologies for reducing emissions, Tonken says these subsidiary companies help the government achieve long-term environmental goals while providing a financial incentive for investors to reap the benefits of developing new cleantech. To date, various industry players, including producers, pipelines and mid-streamers, have invested more than C$150mn (US$118.3mn) in more than 50 promising startups to develop new clean energy technology.

Life in the Wild West

And while Birchcliff’s efforts speak to a broader industry-wide willingness to find practical emissions reductions solutions, they also highlight a fragmented, ad hoc approach in what Tonken admits is a “Wild West” approach among competitors. Even the hamburger industry relies on outside experts to certify its organic and grass-fed options.

It further begs the question: Why hasn’t everybody adopted common reporting and disclosure standards based on independent third-party engineering reporting? Reserves have been subject to similar auditing procedures for many years.

In many ways the industry has already begun to move in that direction, says Peter Schriber, vice president, market development in Canada Xpansiv. Xpansiv is an Australian-based trading platform for data-driven commodity products including, but not limited to, clean energy and carbon credits (including agriculture). In addition, the company offers various certifications through connected bodies such as the Verified Carbon Standard and American Carbon Registry. Until now, the emissions reductions efforts of companies like Birchcliff have been internally audited by its own engineers, but Xpansiv aims to replace that with verifiable data that can be traded on its digital platforms. And while auditing is an important part of the Xpansiv platform, it takes it one step further to make it “tradable” thus increasing its inherent value, both for producers and consumers.

“We are pushing the envelope using technology to create more integrity to the market through continuous monitoring (bottom up and top down), including chemical analysis, production accounting, receipts, nominations, site equipment profiles etc. to get a molecular mass balance of the operations continuously,” Schriber explains. “It's data intensive, in the end it's all about the numbers but you also need to ask yourself as a consumer: How do you know that what you paid for is in fact produced sustainably”?

Schriber says it’s almost inevitable that emissions data will become mandatory disclosure as standards are developed and implemented around the world. “Many factors influence that, of course, such as the multitude of jurisdictions and patchwork of regulation. I think the government naturally also focuses inwards to their jurisdiction first,” he said in an email interview. “We are trying to cut through that by presenting emissions data and other information in a way that cuts across some of those boundaries through the voluntary market in a format that is scalable.”

Markets will decide

Both Tonken and Schriber agree the changes will ultimately be driven by market demand. In 2003, Tonken was formerly chief executive of Big Bear Exploration, whose ill-fated takeover bid of rival Blue Range Resources highlighted deficiencies in the existing patchwork of reserve reporting and disclosure practices. The ensuing scandal resulted in the creation of the Canadian Securities Exchange’s NI-15101 protocol, which set out common – and mandatory – standards for how reserves are evaluated by third-party engineers and ultimately disclosed in public filings.

Schriber agrees standardised reporting and disclosure of emissions data could well become the norm, a lot sooner than conventional wisdom presently admits. The question was put to him: should there also be mandatory disclosure?

“It may end up becoming mandatory,” he said. “Generally what we see is that a lot of innovation occurs in the voluntary market and as it develops both in demand and sophistication at some point, compliance markets and regulators discover there is an efficient way to achieve their policy objectives and things cross over. Once at scale, regulators start to adopt and engage. This could happen much faster in this market than say carbon which has taken 20 years to get standardised benchmark pricing and forward price curves through futures contracts etc.”

Tonken agrees common standards and disclosure might also assuage investors and restore confidence to jittery equity markets leery of the risks associated with climate change policies – escalating carbon taxes are but one example. This is notwithstanding the rise of so-called ethical investing funds and environmental groups that have lobbied big public pension funds such as Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec to divest from fossil fuels by the end of this year. Others, such as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, aim to increase its holdings in renewable energy and clean tech by 2025.

ENGOs seek to starve capital flows

Indeed, Tonken holds a widely-shared view that “the environmental movement is trying to shut down the industry” partly by shutting off capital flows. Due to that uncertainty, he says it’s extremely difficult for traditional upstream energy producers to raise capital on public markets. Ironically, he says it means companies like Birchcliff have to double down on clean tech investments to drive innovation and make it more sustainable – and attractive – over the long run.

Tonken suggests that drive to innovate and increase efficiency will ultimately make or break the business case for emissions reductions in the long run. “Canada (the federal government) certainly isn’t promoting energy (development),” he complains. “That means we have to be more efficient. And at the end of the day the lowest cost producer will be the last man standing.”

The bigger question is whether consumers are prepared to pay more for their energy if need be, knowing it is produced to a higher quality standard? “Yes, there is no doubt, trends are moving to lower carbon, efficient production,” Tonken says. “We’re not doing this to save the world. You can make the business case (for ESG) but very few have been successful executing the business case…we can compete by being better at executing.”

First in a continuing series featuring the work of Gas Pathways Platform participants in advancing natural gas innovation.